June 17, 2024

By Calista Ming, OD, FAAO, FSLS

Photo credit: John D. Gelles, OD, FAAO, FIAOMC, FCLSA, FSLS, FBCLA; Cornea and Laser Eye Institute – CLEI Center for Keratoconus

Since myopia has increasingly been recognized as a global public health issue, more optometrists have begun providing myopia management services in their practices. According to the American Optometric Association (AOA) Research & Information Committee (RIC) survey, 69% of optometrists are providing myopia management services such as low-dose atropine drops, orthokeratology, and multifocal contact lenses.1 This is a wonderful practice opportunity and a great way to get young families more engaged with the practice and in the habit of regular eye exams for their children.

The influx of young patients for myopia management also presents an opportunity to screen these patients for keratoconus (KC). In my private practice in southern California, we focus on specialty contact lenses, including scleral, hybrid, and orthokeratology lenses. We also manage many patients with KC. Clinicians who are just getting into or increasing their OrthoK practice should know that there are at least three good reasons for increased KC screening in this patient population – overlapping risk factors, disease progression, and corneal damage.

1. Overlapping Risk Factors

Doctors are most likely to first discuss myopia control measures with parents when the child is between 5 and 8 years old.1 For very young myopes unable to wear contacts, I may consider atropine first to control myopia progression, starting as early as 4 to 6 years old. Typically, by age 6, children are ready for OrthoK intervention. Once that treatment is in place, children may continue to rely on OrthoK into their teens.

Regardless, children who are good candidates for OrthoK are at an age where myopia is increasing — that, of course, is why we want to slow down or manage the rate of myopic change. However, rapidly increasing myopia, typically a manifest spherical equivalent change of ≥ 0.5D within 12 months, can also be a sign of KC progression.2 Keratoconus often presents around the age of puberty, but it can begin even earlier, in children as young as 6. Before beginning OrthoK, it is important to know if the child has progressive myopia due to axial elongation or due to keratoconus.

2. Disease Progression

Overnight wear of rigid gas-permeable (GP) lenses temporarily reshapes the cornea. It is possible that OrthoK in an abnormal cornea could mask KC, which could lead to a delayed diagnosis. I utilize regular tomography as a standard of care to ensure that posterior corneal changes indicative of keratoconus don’t go undetected during OrthoK wear. We know that KC is a progressive disease that alters the corneal collagen structure. Untreated, it can lead to irregular astigmatism, corneal thinning, permanent vision loss, negative social effects, and potentially the need for a corneal transplant. Early diagnosis and treatment of progressive KC with iLink corneal cross-linking (Glaukos), the only FDA-approved treatment for KC, is critical to preserving vision and corneal stability and, according to modeling, can potentially result in lifetime savings of nearly $44,000 for the patient.3

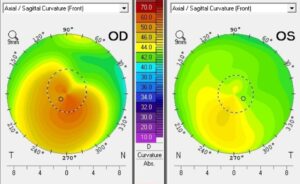

Figure 1: Tomography images of a 15-year-old boy whose myopia was getting progressively worse reveal keratoconus in both eyes, with more advanced disease in the right eye. (click to enlarge)

Without treatment, the risk of rapid progression is actually highest in young people,4-6 so just waiting to see if there are any additional signs of KC while continuing to manage the myopia could be a mistake. Although the safety and efficacy of cross-linking have not been established in patients below the age of 14, research suggests that patients younger than 18 should be treated within six weeks of a progressive KC diagnosis.6

3. Corneal Damage

Adults seeking laser vision correction are screened for KC because the laser treatment can worsen their ectatic disease. Similarly, OrthoK in an ectatic eye can also risk damaging the cornea. Although there aren’t studies specifically evaluating OrthoK in KC, we do have studies evaluating the effects of GP lenses on KC. GP lenses, if fit with excessive apical touch on a cone, can lead to corneal scarring.7 The patient may appreciate an improvement in visual acuity and/or quality, but this form of vision correction is not ideal for the long-term health of the cornea. The goal should be to stabilize the cornea first and then choose a form of specialty lens correction that will be less likely to scar.

Screening and Treatment

Many practices that offer myopia management already have advanced technology that can also be effective in diagnosing KC. Tomography that can detect changes in the posterior surface of the cornea is ideal (Fig 1), but topography is also good at detecting changes consistent with KC. Retinoscopy, a more straightforward tool that all practices have access to, is also quite sensitive. Practitioners should look for a scissor reflex, a poor-quality reflex, one that is different between the two eyes, or an “oil droplet” appearance in the center of the reflex.

Other red flags for keratoconus include the inability to correct to 20/20 at the phoropter, diplopia, or visual quality complaints even when fully corrected, high or rapidly changing astigmatism, unusual autorefractor readings, or a history of atopy. In fact, the association between eye rubbing and keratoconus is strong enough that I encourage my colleagues to ask all young vision-corrected kids about any history of allergy, atopy, or eye rubbing.

When there is progressive KC, cross-linking to stabilize the cornea should be the first step. However, cross-linking won’t necessarily help patients reach their full visual potential. Correction with glasses, soft or GP contact lenses, or specialty scleral lenses may be needed and, in many cases, can take place in tandem with planning for surgery. Detecting and managing keratoconus and vision needs should be a collaborative effort between the primary eye care provider and a corneal specialist.

|

Dr. Ming is in practice at Premier Vision Care Optometry in Lomita, CA. Contact her at drming@premiervisioncare.net. |

References:

- American Optometric Association Health Policy Institute report, 2022. Accessed April 30 at https://www.aoa.org/AOA/Documents/Advocacy/HPI/Doctors-of-Optometry-Embrace-Myopia-Managment.pdf

- Belin MW, Alizadeh R, Torres-Netto EA, et al. Determining progression in ectatic corneal disease. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2020;9(6):541-8.

- Lindstrom RL, Berdahl JP, Donnenfeld ED. Corneal cross-linking versus conventional management for keratoconus: a lifetime economic model. J Med Econ 2021;24(1):410-420.

- Buzzonetti L, Bohringer D, Liskova P, et al. Keratoconus in children: a literature review. Cornea. 2020;39(12):1592-1598.

- Romano V, Vinciguerra R, Arbabi EM, et al. Progression of keratoconus in patients while awaiting corneal cross-linking: A prospective clinical study. J Refract Surg. 2018;34(3):177-180. 3. Buzzonetti L, et al. Cornea 2020;39(12):1592-8.

- Chatzis N, Hafezi F. Progression of keratoconus and efficacy of pediatric [corrected] corneal collagen cross-linking in children and adolescents. J Refract Surg 2012;28(11): 753-758.

- Zadnik K, Barr JT, Steger-May K, et al. Comparison of flat and steep rigid contact lens fitting methods in keratoconus. Optom Vis Sci 2005;82:1014-21.