September 1, 2020

By SooJin Nam, BOptom, MOptom, MBA(Exec)

Long before myopia management developed accepted clinical protocols, optometry managed binocular vision dysfunctions.

Long before myopia management developed accepted clinical protocols, optometry managed binocular vision dysfunctions.

Since the flurry of research around the concept of peripheral hyperopic defocus, myopia research has been admirably single-minded in its pursuit of understanding how to control and conquer myopia progression.1 To some extent, it feels like there were two camps in optometry: one in binocular vision management and one in myopia management. The reality is that many young myopes do not have a single diagnosis and will likely present with co-morbid binocular dysfunctions.

Globally, the prevalence of myopia is estimated to be 34% and high myopia 5%.2 The primary purpose of myopia control is to reduce the risk of potentially blinding ocular pathologies (usually occurring later in life). The most critical risk is associated with retinal detachment and myopic maculopathy.3,4 Both conditions can lead to significant visual loss and measurable reductions in quality of life.5

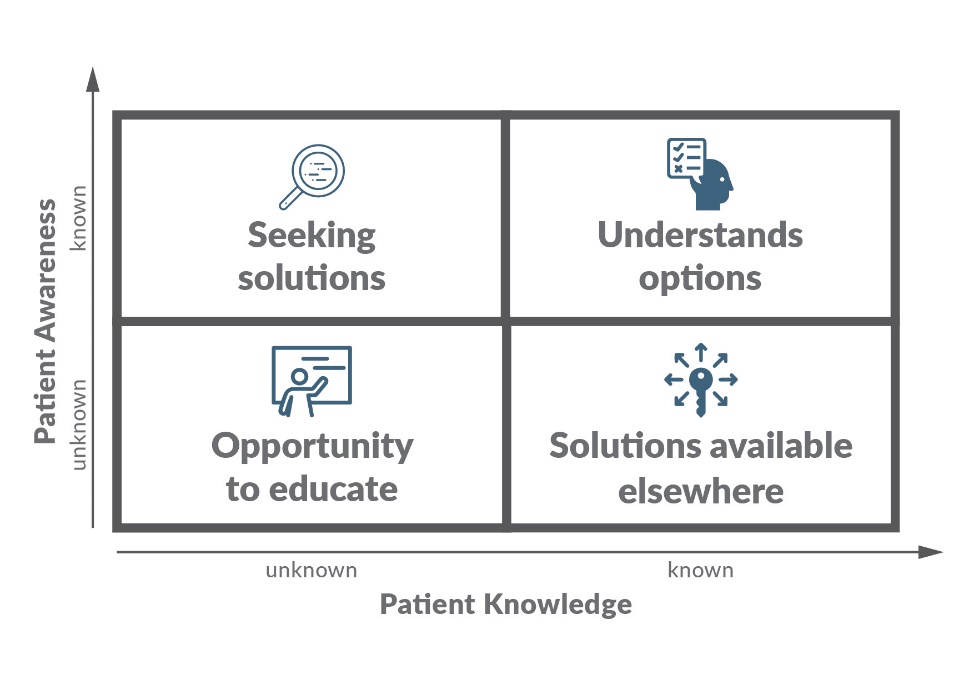

The risk of high myopia (>-6.00D) would be determined against factors such as age, genetics and environment.6 This situation is an “unknown and unmet need” (Table 1) since most parents believe they are protecting their children against wearing thick lenses in the future and not realize it is aimed at decreasing possible visual impairment later in life.

The need to initiate binocular vision management is easier to consider as the patient would likely present with asthenopia symptoms or signs, which would require management with optical lenses, vision therapy and/or visual hygiene advice.7 The prevalence of binocular dysfunctions can vary in school-age students, from 16.6%8 to 34.1%9 for vergence dysfunction and 6%8 to 35.4%9 for accommodative dysfunctions. This is of interest to parents as there is a link between binocular dysfunctions and reduced academic achievement.10 Unlike myopia management, this would be

providing a service for “known and unmet need.” After all, asthenopia symptoms need an immediate solution, whereas blurry vision for distance does not urgently pertain to ocular disease management today.

So the question is not so much whether the clinician should treat binocular vision issues before initiating myopia management but rather that the priority is to address the specific needs of the patient (Table 1). What are their known or unknown needs?

As problem-solving clinicians, it is our role to raise awareness on vision/ocular risks that patients may not be aware of and also educate them on the optometric solutions available.

It is useful to consider the four levels of uncertainty for solving the patient’s perceived problem when providing advice.

There is still an emerging understanding of the changes that occur to binocular vision while wearing a hyperopic defocus myopia management contact lens. Though not conclusive, patients who exhibit esophoria, high AC/A ratio and high accommodative lag have experienced an unexpected improvement in binocular vision findings after wearing OrthoK lenses11,12,13, center distance multifocal contact lenses14, bifocal contact lenses15, progressive lenses16 and and bifocals.17 Atropine, as the only nonoptical myopia management treatment, reduces (instead of normalizing) accommodation and drives esophoria18 and hence would be less desirable in patients with significant accommodative dysfunctions.

There is still an emerging understanding of the changes that occur to binocular vision while wearing a hyperopic defocus myopia management contact lens. Though not conclusive, patients who exhibit esophoria, high AC/A ratio and high accommodative lag have experienced an unexpected improvement in binocular vision findings after wearing OrthoK lenses11,12,13, center distance multifocal contact lenses14, bifocal contact lenses15, progressive lenses16 and and bifocals.17 Atropine, as the only nonoptical myopia management treatment, reduces (instead of normalizing) accommodation and drives esophoria18 and hence would be less desirable in patients with significant accommodative dysfunctions.

Understanding the binocular vision status in young myopes can help determine if a prescribed myopia management strategy will synergistically improve binocular vision or whether additional management is necessary. For example, take extra care of patients with an exophoria vergence presentation as they are more likely to become more exophoric with myopia defocus optical corrections.

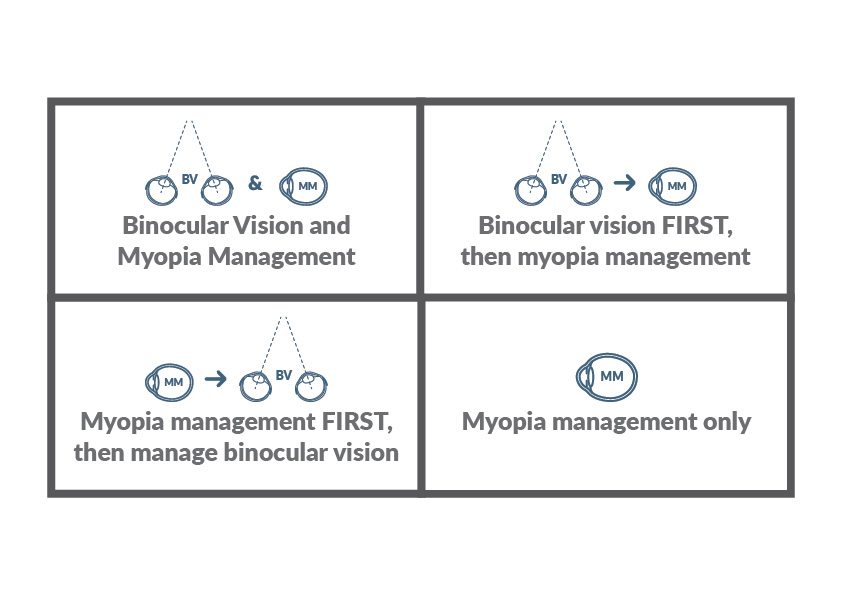

Here are the four management options to consider:

Deciding which clinical protocol to start with should be done in conjunction with the patient’s needs and realistic expectations. Ideally, one would do both at the same time, but factors such as time, finance, expectations and the ability to understand and implement the therapies would be an individual consideration. Consider the learning curve required to learn how to wear OrthoK lenses or the demands on time for the child and parents to complete vision therapy. Families may also have to decide what to prioritize based on their available funds to pay for treatments.

There is one crucial patient group that requires special consideration. This is mainly because most, if not all, myopia management studies specifically exclude patients with strabismus, amblyopia or significant binocular vision issues. For patients with amblyopia or strabismus, the priority may lie in managing their binocular vision to their optimum level before commencing myopia management.

Take, for example, “Matthew” who presented at the age of 9 with early signs of staphyloma in the right eye, significant anisometropia myopia and severe amblyopia, despite several years of monocular patching under ophthalmological care. His mother has high myopia and was keen to consider myopia management.

R -13.00/-1.50×140 R 6/48

L -1.00/-2.00×70 VA 6/9

Where would you start? There is currently no known protocol to provide a myopic anisometropic amblyope with myopia management. Would you provide vision therapy? Would you keep his vision fully corrected with single vision spectacles? Continue with patching therapy? Commence myopia management such as atropine? Consider bifocal spectacle lenses? Recommend center distance multifocal toric contact lenses in the left eye? Would you consider monocular myopia management on the left eye even though the visual acuity is 6/9?

Binocular vision and myopia management should be considered according to patient needs and priorities. Prescriptions and solutions can be optimized based on presenting binocular vision findings and the potential risk of visual impairment due to myopia.

Soo Jin Nam, B.Optom, MOptom, MBA(Exec), is the director of Eyecare Kids in Sydney, Australia, Treasurer/State Councillor (Optometry NSW/ACT).

References:

1 Walline JJ. Myopia Control: A Review. Eye Contact Lens. 2016;42(1):3-8. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000000207

2 Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):1036-1042. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006

3 Saw SM, Matsumura S, Hoang QV. Prevention and Management of Myopia and Myopic Pathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(2):488-499. doi:10.1167/iovs.18-25221

4 Ikuno Y. OVERVIEW OF THE COMPLICATIONS OF HIGH MYOPIA. Retina. 2017;37(12):2347-2351. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001489

5 Williams K, Hammond C. High myopia and its risks. Community Eye Health. 2019;32(105):5-6.

6 Morgan IG, French AN, Ashby RS, et al. The epidemics of myopia: Aetiology and prevention. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;62:134-149. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.09.004

7 Scheiman, Mitchell, and Bruce Wick. Clinical management of binocular vision: heterophoric, accommodative, and eye movement disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

8 Scheiman M, Gallaway M, Coulter R, et al. Prevalence of vision and ocular disease conditions in a clinical pediatric population. J Am Optom Assoc. 1996;67(4):193-202.

9 Jang JU, Park IJ. Prevalence of general binocular dysfunctions among rural schoolchildren in South Korea. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2015;5(4):177-181. doi:10.1016/j.tjo.2015.07.005

10 Shin HS, Park SC, Park CM. Relationship between accommodative and vergence dysfunctions and academic achievement for primary school children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2009;29(6):615-624. doi:10.1111/j.1475-1313.2009.00684.x

11 Brand, P. “The effect of Orthokeratology on accommodative and convergence function.” A clinic based pilot study. Behavioural Optometry 12.1 (2009): 8-15.

12 Gifford, Kate, et al. “Near binocular visual function in young adult orthokeratology versus soft contact lens wearers.” Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 40.3 (2017): 184-189.

13 Felipe-Marquez, Gema, et al. “Binocular function changes produced in response to overnight orthokeratology.” Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 255.1 (2017): 179-188.

14 Cheng, Xu, Jing Xu, and Noel A. Brennan. “Accommodation and its role in myopia progression and control with soft contact lenses.” Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 39.3 (2019): 162-171.

15 Aller, Thomas A., Maria Liu, and Christine F. Wildsoet. “Myopia control with bifocal contact lenses: a randomized clinical trial.” Optometry and Vision Science 93.4 (2016): 344-352.

16 Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial 2 Study Group for the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. “Progressive-addition lenses versus single-vision lenses for slowing progression of myopia in children with high accommodative lag and near esophoria.” Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52.5 (2011): 2749.

17 Cheng, Desmond, et al. “Effect of bifocal and prismatic bifocal spectacles on myopia progression in children: three-year results of a randomized clinical trial.” JAMA ophthalmology 132.3 (2014): 258-264.

18 Yam JC, Jiang Y, Tang SM, et al. Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) Study: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% Atropine Eye Drops in Myopia Control. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.05.029